Searching for Methane Hydrates of Cascadia Margin

Bubble streams have been observed in the sonars of Oregon fishers for several decades but it's only in recent years that scientists have begun to explore and understand their source along the Cascadia Margin: methane seeps and hydrates.

“We have been looking for hydrates on all of our dives so far. This is a big moment to be able to find a deposit that is both this accessible and also this big,” said Corps of Exploration member Megan Cook.

But what exactly is a methane hydrate?

“It’s basically the solid form of the methane that we’re seeing bubbling out here. When the methane is exposed to a certain pressure and temperature conditions, and also there is a high enough concentration of methane, it can form the solid form which is methane ice,” explained Dr. Tamara Baumberger, assistant professor at Oregon State University and Research Scientist at NOAA's Pacific Marine and Environmental Lab. “If you look at the molecule, it’s basically a methane molecule surrounded by a lattice of ice.”

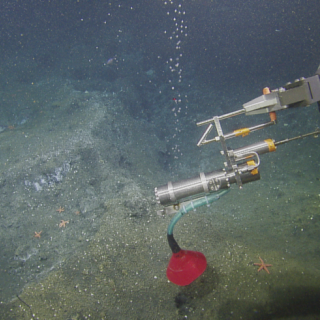

Solid methane hydrate outcrops can resemble an ice cube or even a snow cone of shaved ice. And what these samples hold is an encyclopedia of information about their unique underwater worlds. While diving at a depth of 1600 meters near the southwest ridge of Gray's Canyon along the Cascadia Margin, we collected an “entire suite of samples,” including methane hydrate ice and a sample of nearby bubbles to compare solid and gaseous methane. Our team also collected water samples to understand dissolved methane and the chemistry of the area, as well as changes in the gradient to determine how widespread of an impact the seep has in its environment.

But it’s not all just bubbly fun on the seafloor! At a depth of 786 meters, our team saw hundreds of sea stars seen across the seafloor of the north rim of Astoria Canyon.

“This is just crazy! The seafloor is practically pink with sea stars,” said Susan Merle, a senior research assistant at NOAA's Pacific Marine and Environmental Lab and Oregon State University’s Cooperative Institute for Marine Resources Studies.

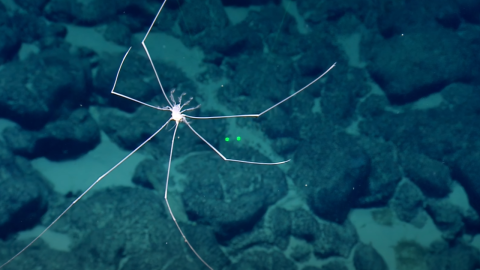

And who could forget the school of “sablefish scientists” and that overly friendly deep-sea crab hugging their fishy friend?

Cascadia Margin Seep Exploration

For two weeks, E/V Nautilus will return to the Cascadia Margin, a geologically active region located offshore of Washington, Oregon, and northern California, where we have mapped and explored many methane seeps and cold seeps.