Remembering Titanic: A Sub Pilot's Story

Over the years, E/V Nautilus has been home to some of the most influential scientist, engineers, and pilots in ocean research and exploration. Today, on the 103rd anniversary of the sinking of RMS Titanic, we had the honor of interviewing Will Sellers, the first sub pilot to survey the wreckage. Will's story recounts the challenges, excitement, and legacy of his dives along with Dr. Bob Ballard and Martin Bowen in July of 1986. Will Sellers now brings his years of experience to the E/V Nautilus and our ROV and Engineering Intern program. One of the few "teaching hospitals" for ocean exploration, the interns aboard Nautilus are able to get hands on experience piloting ROVs and learning from leaders in the industry.

Included below is a transcript of Will's memories of his first time seeing Titanic while piloting Alvin on his first dive to the wreckage site on July 10, 1986:

"When news broke that Bob Ballard on the R/V Knorr had found the RMS Titanic rumors immediately started that WHOI (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute) would go back to the wreck the one year later with the DSV Alvin.

Ballard’s Deep Submergence Lab or DSL at Woods Hole was developing a new toy called Jason Jr., a small remotely operated vehicle (ROV) that would be a test bed for the concept of using fiber optics in the deep ocean. This research would eventually lead to Nautilus's own ROV's Hercules and Argus. Ballard's team planned to put Jason Junior on the front of Alvin and use it to explore the interior of the wreck. This would allow researchers to go places that would be too dangerous for Alvin to venture. There were many safety considerations for this ambitious project. Mainly that the entire Jason Jr. system would replace Alvin’s sample basket. In the event that the ROV should become entangled and irretrievable, the entire system would have to be jettisoned and so that Alvin could surface safely. This would be a big loss, but that’s the way it has to be, this is a risky business.

Because of the weight of the Jason Jr. system, we had to remove Alvin’s port manipulator. This was no big deal, as the policy for the Titanic expedition was to take nothing from the wreck and leave it as we found it. We still had the starboard arm for any emergency. A video camera and lights were mounted on the arm so that we could use it as a pan and tilt to aim the camera at Jason Jr. and film the ROV working. This arrangement was dubbed Big Bird.

The Atlantis II left Woods Hole on the 6th of July 1986 for a four day transit to the dive site. The weather was fine and we made good time. Good time in the oceanographic world is about 12 knots, slow by commercial standards, but economical. The first dive was done by senior pilots Ralph Hollis, and Dudley Foster, and chief scientist, Bob Ballard. Unfortunately, no sooner did they sight the forward half of the wreck; Ralph had to call up to the surface controller saying he had problems in the battery tank #2. The dive had to be cut short. A battery fault is a serious glitch. We got Alvin back on deck by noon and began to diagnose the problem. It turned out that the battery tank had partially flooded and would have to be changed. This had never been done at sea before, only at the dock. A battery tank weighs 2,400 pounds in air and having it swing around beneath the sub on a pitching, rolling ship is no one’s idea of a fun time. A hatch in the main deck had to be opened with Alvin positioned over it so that the battery could be lowered into the hold and be serviced. Luck was with us. The sea state that day was fairly calm, a rarity for the North Atlantic. We worked through the night and had the sub ready to dive the next morning.

On the second dive, Dudley Foster was the pilot with Martin Bowen and Bob Ballard as his passengers. This day, Alvin would perform flawlessly, but Jason Jr. had problems and was nearly lost on recovery due to trouble with the latching gear that kept it in its cage on the front of Alvin. The recovery swimmers managed to save it and bring it home in the small boat. So much for dive two. Tomorrow it would be my turn.

On July 10th, I made the third dive down to Titanic. After a routine pre-dive and launch, by 7:30 AM my two observers, Bob Ballard and Martin Bowen, and I were on our way to the bottom. Heading to the bottom in Alvin is actually pretty relaxing. Well, relaxing as you can get in a six-foot sphere. It is still warm inside, not yet cooled off by the cold temperatures of the deep ocean. Once you flood the ballast tanks and sink, you leave behind the motion of the waves and begin the two and one half hour free fall to the bottom. The Titanic lies at a depth of 3996 meters, about 2.5 miles down.

The sphere was very crowded on these dives. Not a roomy place to begin with, it has an inside diameter of 6 feet, 1 inch and half of that space is consumed by all the electronic systems necessary to run the sub as well as life support for three days. We never had so many video cameras and VCRs working on the sub before. Both Martin and Bob were sitting in the back of the sphere with cases of videotapes sitting on their laps. There was nowhere else to put them. I even had our lunch bag hanging over my head, tied to the hatch handle.

As we were passing through 3000 meters, the surface controller, who is tracking us and plotting our position, calls down from the ship and tells me to drive east for a couple of minutes, as it looks like we are coming right down on top of the forward half of the wreck. Titanic lies in two pieces about a mile apart. We were headed for the bow section. It is over 400 feet long and standing upright with a slight list to port. After getting an all clear from above, I turned Alvin to face the wreck.

The minutes tick by slowly. We are full of anticipation about the day’s work ahead of us. I have seen a lot of strange and wonderful things on the bottom of the ocean, but this will be the icing on the cake. At an altitude of 50 meters above the seafloor, I dropped the first of two, 250-pound weights. This slows our descent. At 25 meters, I dropped the second one.

Once I got the sub neutral, I said to Bob and Martin, “Well, let’s see how this thing handles.”

Martin replies, “What! You mean you never drove this thing before?”

Alvin having just gone through a major overhaul, where the big 42-inch stern prop controlled by toggle switches was replaced by a high-tech system of seven smaller thrusters controlled by a joystick. Alvin became a different machine from that transformation. I had taken two months off at the end of the overhaul, and this was my first chance to drive the “new sub.”

“Relax” I told him, “If you’ve driven one, you’ve driven them all.” Well, not really, but I am lucky to have a good intuitive feel for this sort of thing. It was no problem at all.

The Titanic was the biggest sonar target I had ever seen. It more than filled the screen. The only way to get a full image would be to drive away and look at it from a greater range. Bob Ballard had been studying the Titanic for years and had done the two shorter dives with Ralf Hollis and Dudley Foster. He had a pretty good feel for the wreck in general and started to give me directions to the first area he wanted to explore. I had been to the bottom with Bob before on other expeditions. He has probably made more deep dives in more submersibles than any other man, alive or dead. I was glad to have him with me.

The first thing to do was to acquire the wreck visually. I drove across the bottom while glancing at the sonar and watching the Titanic come closer on the screen until what looked like a huge wall appeared in front of me. This was the starboard side of the wreck. Covered in thick rust, it rose up in front of me out of view. I pulled up close, about six feet away, to the point where we were getting good close up video from Jason Jr., which we had powered up just before we reached the bottom. As we rose straight up, we saw that the hull was covered in a thick coat of orange rust. This rust was so fragile that just the motion of us passing closely was enough to dislodge it from the hull and decrease visibility. I had to move this 18-ton sub slowly and carefully if we were to get any useful footage.

We passed the first row of round portholes about 20 feet up from the bottom. Continuing up another 15 feet was a row of rectangular windows, all with their glass intact. We didn’t stop to examine these, as we couldn’t shine enough light inside to see anything. Twenty feet above those windows, we finally came to the rail for the lifeboat deck.

The excitement level was high here. We were looking at a dramatic point on the ship that had not been seen in 75 years. People have asked me what I was feeling at this time. I have heard Martin and Bob talk about their feeling of awe in seeing the place where so many people had lived the last desperate moments of their lives, but at the time I felt none of this. I had a job to do.

The biggest danger to any dive on Alvin is entanglement on the bottom. If I were to get us stuck and was unable to free the sub, we would become a bit of Titanic history ourselves. Titanic is so far from land and so deep that there would be no real chance of rescue, only a recovery of the sub and our bodies. Needless to say, I had a lot on my mind and did not have the luxury of waxing romantic at the time.

I hopped the sub up over the rail and set down on the forward end of the starboard lifeboat deck, facing aft. Secure in our parking spot with all systems go, it was time for Martin to go to work and deploy Jason Jr. On the previous two dives, Jason Jr. had some troubles and was not deployed for more than a few minutes. Today it would work flawlessly. Sitting behind me to the right, Martin had his control box sitting on his lap. He flew Jason Jr. out of its cage and down the life boat deck to the full length of its tether, about 130 feet, and turned around. It was an amazing sight. With the quartz lights available at the time, the furthest you could see from the Alvin was about 50 feet, and the edge of that were shadows. When Jason Jr. turned around, the whole distance between us was illuminated. We could see over 100 feet and see Alvin sitting there on the lifeboat deck in J.J.’s video. As well lit as it was, the effect was spooky, as the lights create as many shadows as they illuminate things.

Martin flew Jason Jr. up to the square windows on the bulkhead behind the lifeboat davits. Some had glass, while others did not. The glass was so clear, that Jason Jr. would bump right into it before we could tell it was there. Looking in one window, we could see a pummel horse. This must have been a gymnasium.

After exploring as much as we could from that spot, it was time to move Alvin. Bob Ballard was right on top of his game here and didn’t want to waste a minute. Martin reeled Jason Jr. into its cage and I lifted us off the deck and headed for the bridge. All the structure of the wheelhouse was gone, ripped off in the violent action of sinking or eaten by wood boring worms. All that remained was the engine room telegraph and steering mechanism. I landed next to that, and Martin deployed the ROV again. This time, we explored the bridge area and the cargo cranes just below us and forward. When looking through a video camera, as on Jason Jr., it is sometimes hard to get a feel for the scale of things. Looking down on the cargo cranes, they looked like pieces of an erector set, but were actually as long as the ship was wide. One gets a better perspective from looking out of Alvin’s view ports.

Our next directive from Dr. Ballard was to explore the bow. I lifted off the bridge deck fighting a slight current, maybe a quarter knot, and drove forward to the peak of the bow. We landed gently by the open cargo hatch. With the hatch cover gone, this looked like a great opportunity for Jason Jr. to penetrate into the wreckage for the first time. After an inspection, however, it proved that it wasn’t going to happen on this dive. The cargo hold was full of debris and mud, almost to the hatch level. We were disappointed because the ship’s manifest showed a luxury car and other items that would have been interesting to see after all those years.

While sitting there, Martin flew Jason Jr. over the rail to look for the name of the ship painted on the side. We searched most of an hour, but came up empty handed. The paint evidently did not survive the years.

Our time on this dive was running out. It was almost 3 PM and time to start the 2.5 hour ride to the surface. I lifted off the deck, cleared the port rail and drove away from the wreck. To get home, I had to drop two 250 pound steel weights. We didn’t want to pollute the site with them, so I drove off at least 100 m to a clear area with no debris and let them go. After calling the surface to tell them we were on our way up, we sat back and talked over what we had seen that day. It was a very successful dive and all three of us couldn’t wait for the chance to do it again. Martin and Bob would go the next day, but with a different pilot. I would have to wait five long days for my slot to come up on the rotation again."

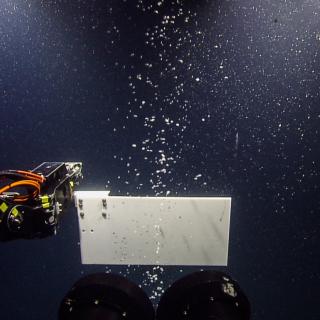

GISR: Natural Gas Seeps in Gulf of Mexico

What impact do natural hydrocarbon seeps have on the ocean and atmosphere? This is one of the key questions we’ll be investigating on this leg of the expedition. This expedition is part of the Gulf Integrated Spill Response (GISR) Consortium, funded by the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). The vision of the GISR Consortium is to understand and predict the fundamental behavior of petroleum fluids in the ocean environment.