Discover Galveston's Hidden Pirate History

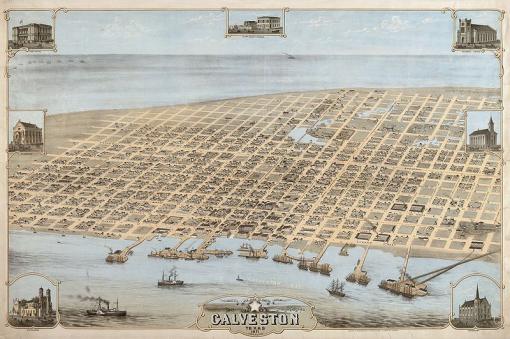

The port of Galveston, TX might look familiar to Nautilus Live viewers - it was a major point of departure for the first half of our 2013 expedition season. The city of 47,000 looks like many of its mid-sized American counterparts, but behind its cruise ships and historic buildings lies a sordid origin story: the area’s first permanent settlement was a hub of smuggling and privateering, a 19th century pirate island.

Much of the original construction on the island happened under the command of Louis Michel Aury, a Parisian pirate working with Mexican rebels in their fight for independence from Spain. In 1816 the revolutionary Mexican Republic lay claim to Galveston and named Aury governor. His brief command of the island was plagued by discontent, and when he returned from an expedition down the Mexican coast he found many of his men had deserted him for a new leader - another pirate, the swashbuckling Jean Laffite. Aury abandoned his post at Galveston but continued to aid revolutionary causes until his death (in one notable incident he aided notorious Scottish conman Gregor McGregor in an invasion of Spanish Florida - a discussion of McGregor’s exploits is far beyond the scope of this blog, but The Economist did a great write up a few years ago available here).

Before reaching Galveston, Laffite made a name for himself as a privateer, running a successful smuggling operation out of Barataria Island (south of New Orleans) alongside his older brother, Pierre. In a self-serving attempt to avoid legal prosecution for himself and his men Laffite supported the American effort in the War of 1812, and was instrumental in Andrew Jackson’s famed victory over British forces at the Battle of New Orleans.

After the war the Laffite brothers entered into the employ of the Spanish Crown as spies, and in 1817 they established their foothold on Galveston island, renaming the colony “Campeche” (named after but not to be confused with the Mexican state). They quickly turned back to their old habits, and Jean Laffite became the leader of the island, rebuilding and refortifying the settlement. He had a house built for himself, a two-story compound named Maison Rouge. Readers with some French background might have figured out the defining feature of the house - it was painted red and was apparently very difficult to miss. All newcomers took loyalty oaths to Lafitte, which he rewarded by issuing his men Letters of Marque. This allowed ships leaving from Galveston to “legally” prey upon ships of any country. For all intents and purposes Galveston was, for several years, a bonafide pirate island.

Of course, our European pirates weren’t the first inhabitants of the island - it was long home to members of the Karankawa tribe. The two groups coexisted peacefully for much of the pirates’ run, with one notable exception: In 1819 three-hundred Karankawa warriors attacked Maison Rouge. The reason for the attack? The pirates had kidnapped a Karankawa woman and were holding her in the compound. Although the pirates were outnumbered, they soon overwhelmed the native warriors with superior armaments.

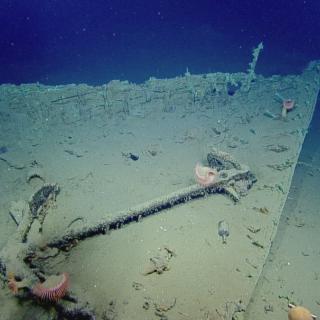

Here’s another interesting potential Nautilus connection - remember the Monterrey Wrecks we visited in July? Monterrey B, a smaller ship, was loaded down with cattle hides, horn, and tallow, all common cargo items in the Gulf of Mexico at the time. More research is needed before the archeological team can say with certainty, but it’s possible that these ships were bound for the pirate island before their stormy demise.

Lafitte’s reign could only last for so long - the U.S. Navy had long kept an eye on Campeche, and after the Adams-Onís treaty between the U.S. and Spain upped the punishments for piracy and privateering many of the young South American nations who had been using the privateers stopped issuing Letters of Marque. Soon after this Lafitte found himself broke and decided to relocate. He worked out a deal with the U.S. Navy to let him leave unpunished, and they sent USS Enterprise (the first of her name) to ensure that he actually left. On their way out the pirates burned the community, including Maison Rouge, to the ground.

Galveston didn’t stay abandoned for long, first becoming part of Mexico, then the independent Texas, then eventually joining the United States. Before long it was an important shipping port, a home for legitimate merchant activity far from its pirate past. Many years later, it would be home to the 2013 season launch of E/V Nautilus.

And what happened to Lafitte? He continued his plundering ways, finally admitting to his crew that he did not have a legitimate Letter of Marque and that they were indeed pirates, not privateers. About half of his men were put off by the legal distinction and left. Lafitte wasn’t ungrateful - he gave them a ship on which to depart (which he then had his men cripple - they were pirates, after all). Ironically, several years later he took a commission with the Colombian Navy, finally becoming a true privateer.

His death remains shrouded in mystery - reports vary, with some saying he was lost at sea in 1825, and others that he died on the mainland soon after of a crippling illness. At this point; however, his reputation had superseded his actions - according to rumors at the time he changed his name and escaped, with some people going so far as to suggest that he had sailed to Saint Helena, rescued Napoleon, and settled down with him in Louisiana. No evidence supports any of the rumors, but the legend had a life of its own. He’s still remembered to this day with portrayals in novels, films, and video games, not to mention a Louisiana town, a National Historical Park and Preserve, a famous New Orleans Bar, and true immortality as a member of Cap’n Crunch’s cereal crew.

Want to learn more about Galveston’s history or its pirate leaders? Check out these articles from the Texas State Historical Association:

- Galveston: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/rrg02

- Aury: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fau04

- Lafitte: http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fla12

Special thanks to Amy Borgens for her help in verifying or correcting much of the historical content of this post.

Shipwreck 15577 - The Monterrey Wreck

The Discovery

In April 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ship Okeanos Explorer conducted the first reconnaissance of shipwreck site 15577 as part of an interdisciplinary exploration mission focusing on deepwater hard-bottom habitat, naturally occurring gas seeps, and potential shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico.